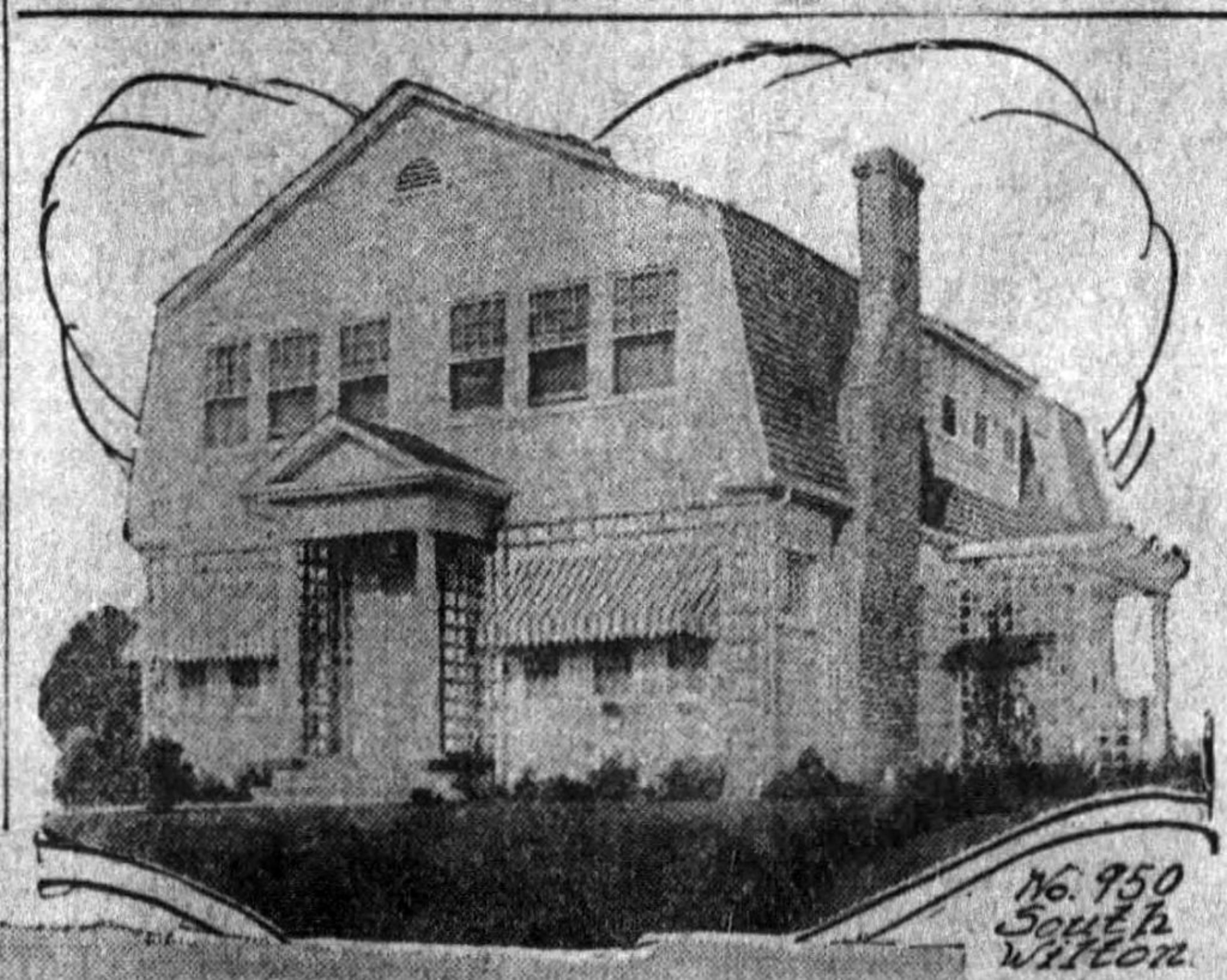

In December of 1916 it is announced that Andre H. Cuenod—a Swiss lumberman who came to Los Angeles in 1891—was putting up this nifty Colonial he’d designed himself. The two-story, seven-room $4000 frame residence would feature a concrete foundation, shingle roof, hardwood floors, hardwood and pine trim, and mantel. (The picture above from a January 1918 blurb in the _Times_ about how he’d sold his place to M. S. Phillips for $9000. Tidy little profit.)

One hundred years and change later, she still stands proud, with her great gambrel roof and dentil-filled pedimented entryway. Even has all her original windows and giant chimney!

Sure the lawn has turned to brick and they’ve glassed in the side pergola, but that ain’t the end of the world

Not crazy about all the white paint, but that’s an easy fix. And no can lights! This could be a breathtaking room.

A shot of an upstairs bedroom. Jeeps, it’s as big as a football field. But God forbid we have genteel living and room to swing a cat in this lifetime; density Nazis won’t be happy till we’re all living in the same airless cubicles we work in. “But it’s micro-living! It’s good for the environment!” No it’s not, Obergruppenführer.

So where did I get interior shots? From the realty listing. But where one sees all this restoration potential—what’s the point in them? Who is buying this to live in it, especially when it is marketed as a teardown:

Dream Realty, La Crescenta

I don’t have to tell you, I suppose, where the story goes next. Coming soon, its five-story, twelve-unit replacement.

About Nathan Marsak

NATHAN MARSAK says: “I came to praise Los Angeles, not to bury her. And yet developers, City Hall and social reformers work in concert to effect wholesale demolition, removing the human scale of my town, tossing its charm into a landfill. The least I can do is memorialize in real time those places worth noting, as they slide inexorably into memory. In college I studied under Banham. I learned to love Los Angeles via Reyner’s teachings (and came to abjure Mike Davis and his lurid, fanciful, laughably-researched assertions). In grad school I focused on visionary urbanism and technological utopianism—so while some may find the premise of preserving communities so much ill-considered reactionary twaddle, at least I have a background in the other side. Anyway, I moved to Los Angeles, and began to document. I drove about shooting neon signs. I put endless miles across the Plains of Id on the old Packard as part of the 1947project; when Kim Cooper blogged about some bad lunch meat in Compton, I drove down to there to check on the scene of the crime (never via freeway—you can’t really learn Los Angeles unless you study her from the surface streets). But in short order one landmark after another disappeared. Few demolitions are as contentious or high profile as the Ambassador or Parker Center; rather, it is all the little houses and commercial buildings the social engineers are desperate to destroy in the name of the Greater Good. The fabric of our city is woven together by communities and neighborhoods who no longer have a say in their zoning or planning so it’s important to shine a light on these vanishing treasures, now, before the remarkable character of our city is wiped away like a stain from a countertop. (But Nathan, you say, it’s just this one house—no, it isn’t. Principiis obsta, finem respice.) And who knows, one might even be saved. Excelsior!””

Nathan’s blogs are: Bunker Hill Los Angeles, RIP Los Angeles & On Bunker Hill.